In 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court held that a public school funding system based primarily on local property tax revenues does not violate the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause on the basis that education is a fundamental right, which prosecutors claimed it to be. Since before and after this precedent, every state (with the exception of Hawaii) has relied heavily on local property tax revenues to fund public schools. Such a system has created what many school districts view as an unequal distribution of wealth that amounts to wealth-discrimination, as more affluent school districts with more businesses and higher residential property values have been able to raise more money from local sources than poor districts for more than forty years now.

As of 2013, most public school districts maintain a higher population of Blacks, Latinos, or Native Americans than Whites. In other words, the majority of American public schools appear segregated in the second decade of the twenty-first century, with students of color comprising over 90 percent of student populations in some districts, and the vast majority of those students designated by federal and state sources as “low-income.” In order to highlight overarching connections between public school funding and racial groupings, we’ve studied and assembled trends that we find vital to understanding the relationship between public education and race in 2015.

Majority-Low Income Schools Coincide with Majority-Minority Schools in Both South and Nation

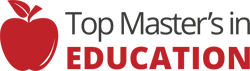

Nationwide, over two-thirds of students of color attend schools where the proportion of low-income students is more than one in every two. This means that 72 percent of Black students, 68 percent of Hispanic/Latino students, and 65 percent of Native American students all come from households where income is over 100 percent lower than the federal poverty line. While national numbers reflect an increase in representation of minority populations in public schools and may appear progressive since Whites have historically dominated public school populations, they’re not–especially for urban public schools, where the majority of students (59.8 %) are low-income, and the overwhelming majority of students are people of color who attend majority-minority schools, or schools where at least 50 percent of students in attendance are from ethnic or racial minority groups.

According to data from the National Center for Education Statistics, low-income students accounted for close to half (48%) of national public school enrollment in 2011. But after two years of averaging a +1.5% annual rate increase of students beneath the federal poverty line, low-income students accounted for over half (51%) of national public school enrollment in 2013. For the South, these numbers are nothing new. According to data sets from the same organization, the region has maintained low-income students as the majority in its public school system since 2007, meaning that one in every two public school students in the South has come from a low-income household for nearly a decade. And public school students in the South have only gotten poorer since 2007, as the majority of students living in low-income households grew at an average annual rate of +2% between 2011 and 2013, from 53% to 57%.

De Facto Segregation has Left Behind “Educational Ghettos”

In 1968, the year the Civil Rights Act was signed, 76.6 percent of Black students and 54.8 percent of Latino students attended public schools where the majority of students in attendance were minority students (i.e., non-Whites). The number of students of color in majority-minority schools has remained virtually unchanged since 1968, with only 2.5% less Black students attending these schools over the past forty-five years. Meanwhile, Latino students have become increasingly more segregated from their non-Hispanic White peers than they were over forty years ago. 79.1 percent of all Latino students attended majority-minority schools in 2010. That means there has been a 24.3 percent increase in the level of segregation between Whites and Latinos since the Civil Rights Act was signed.

Levels of both race and class-based separation have increased since the Civil Rights Act. In 2015, separation more often appears class-based, and in 2014, disparities between high and low funded public schools led South Carolina’s Supreme Court to decry its own poor, majority-minority districts as “educational ghettos,” or substandard by the Department of Education’s guidelines. Even worse: in supermajority-minority public schools–schools where students of color make up 90 percent or more of the student population–the number of Black and Latino students in attendance increased 4.9% and 14.2%, respectively, between 1980 and 2009. In 2005, 88 percent of supermajority-minority schools were associated with levels of poverty characteristic of educational ghettos, which was not the case for White-dominated schools.

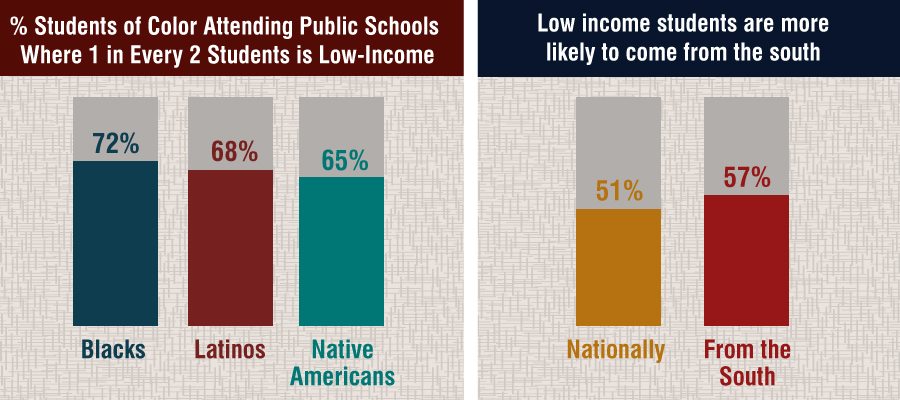

Using the latest data available from the National Center for Education Statistics, local property tax revenues, despite coming from smaller geographical areas, still serve as the main source of local funding, comprising over half of the 44 percent allocated for public education. The funding pool’s remainder is filled in by state (45%) and federal sources (11%). But twenty-three out of fifty states–that’s 46 percent of the United States’ public school systems–are still majority-funded by local property taxes. The variability between local property values accounts majorly for these vastly different public school districts, whose wealth distributions correlate directly with differences of race and class.

Straining large shares of revenue from small-time local property taxes is largely responsible for “have” and “have-not” public schools that cannot spend equally on individual students. Because so much public school funding relies on district-by-district property wealth, those districts with high levels of property wealth are able to spend tens of thousands more on individual students than districts with low property wealth. Since the Civil Rights Act of 1968, white flight from urban to suburban neighborhoods, private schools, and a small number of affluent, majority-White public school districts has contributed in large part to the foundation of this class-system of property wealth inequality. In other words, class-based resegregation has led to the current problem of unequal funding among and de facto segregation within today’s public school districts.

Less Money, More Problems Create School-to-Prison Pipeline

According to a data snapshot from the Civil Rights Data Collection in 2014, black students are over three times more likely to be suspended than their White peers. Even in more affluent schools where White students are the majority, Black and Latino students face steeper punishment than their White peers. Black and Latino students also tend to receive more severe punishments for less serious and more subjective offenses, such as “defiance” or “insubordination,” which are most open to interpretation, have been shown as most capable of being influenced by institutional racial biases, and often go unnoticed by less qualified teachers and administrators. According to multiple studies, less qualified teachers working in high-poverty districts are also more likely to be hired at majority-minority public schools than higher qualified teachers in wealthier districts. Less qualified teachers also tend to be paid lower salaries and be less equipped to handle situations where discipline is required, meaning that disciplinary action at majority-minority schools often falls into the hands of local law enforcement.

Because of having to resort to underqualified, underfunded teachers, schools with a majority of low-income Black and Latino youth are forced to rely disproportionately on extensive use of suspensions, expulsions, and the police. Largely due to the threat of school shootings, the percentage of students of all races reporting the presence of law enforcement personnel in their school has increased over 15 percent between 1999 and 2011. However, in many urban school districts such as those in New York City or Chicago, supermajority-minority school administrators have placed local law enforcement in charge of security and enforcing disciplinary measures, placing an additional burden on school budgets in the form of School Resource Officers (RSOs), whose presence on school campuses has been shown to push more students through what is known as the school-to-prison pipeline.

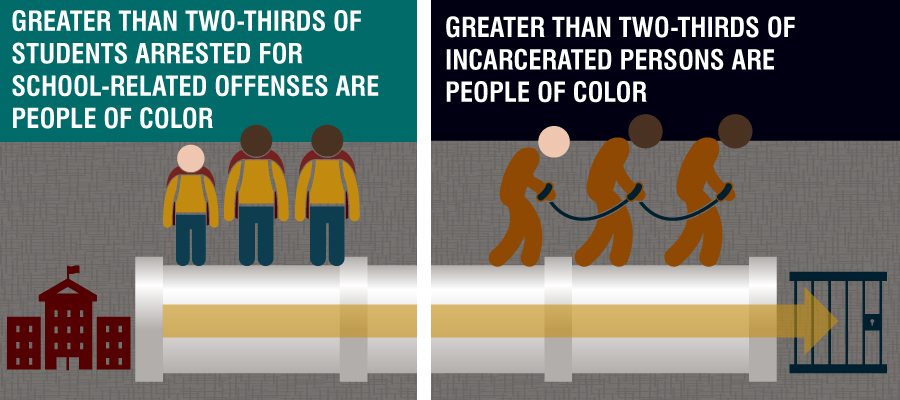

Such measures have made supermajority-minority schools resemble prisons not only in the way of taking severe penal action, but also in terms of demographics. According to a 2012 report put out by the Civil Rights Data Collection, African-American students made up only 18 percent of the total student population between August 2009 and June 2010, but bore the brunt of the severest disciplinary action during that school year. Black students experienced 46 percent of total multiple out-of-school suspensions and 39 percent of total expulsions. If we compare those percentages with the relatively reduced 29 percent of total multiple out-of-school suspensions and 33 percent of expulsions experienced by White students who make up more than half of the total student population (51%), then we see significant disciplinary disparities between White students and students of color. During the 2009-2010 school year alone, students of color (i.e., Blacks, Latinos, and Native Americans) represented under half of the U.S. student population (49%) but comprised over 70 percent of school-related arrests or referrals to law enforcement. This means more than two out of every three students (and nearly three out of four) who received the most severe disciplinary action–i.e., invocation of state or federal penal institutions–were Black, Latino, or Native American.

It is uncanny how closely disciplinary disparities in U.S. public schools resemble the penal disparities in U.S. prisons. According to the 2010 report put out by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, non-Hispanic Whites represented under one-third (32%) of the total incarcerated population despite comprising well over half (63%) of the total U.S. population. Blacks, on the other hand, represented an estimated 38 percent of the total incarcerated population, which is over three times the 12 percent of the U.S. population the group represents. Meanwhile, Latinos comprised an estimated 22 percent of the total incarcerated population, and Native Americans represented an estimated 8 percent of the total incarcerated population. This means that even though Blacks, Latinos, and Native Americans comprised well under half of the total U.S. population (~37%) in 2010, they disproportionately comprised over half (~68%) of the total prison population, meaning that for every non-Hispanic White person in prison, more than two others will be Black, Latino, or Native American. This ratio of greater than two in every three is practically identical to the proportion of students of color to White students who are arrested or referred to law enforcement in today’s public school system.

With numbers like these, it’s no wonder we link school and prison via the concept of a pipeline.

All Signs Point Toward Reform

Every source linked above has drawn attention to the fact that disparities in public school funding widen on the basis of local property value, race, and class. Most have also offered solutions that would provide greater equity in educational opportunities. These solutions include enacting legislation that would distribute more state and federal wealth to districts with low property values; increasing teacher pay and qualification standards for low-income districts; and providing smaller class sizes along with more social service positions (e.g., counselors and nurses) for majority-minority schools. Some gains have already been made on the first of these accounts. According to a joint report put out by the Leadership Conference Fund and the Education Law Center, fourteen states are currently defending themselves in educational equity cases, meaning that local parents are taking a stand against unequal funding for low-income districts. But we still have a long way to go.

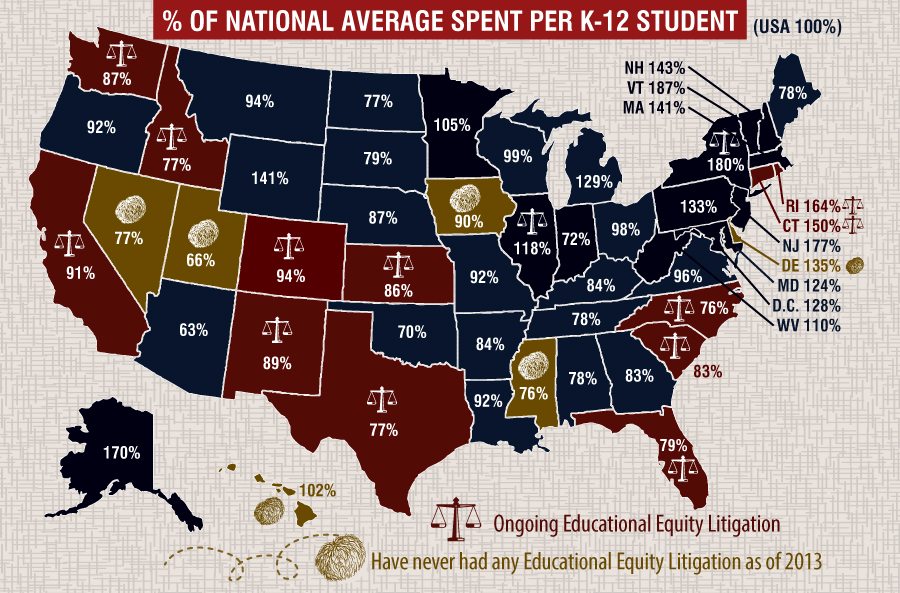

More than one in every four states with ongoing litigation for educational equity maintain above average expenditures per student. Meanwhile, two in every three states that have never had any litigation filed for education equity maintain below average expenditures per student. Among the eighteen states that maintain above average expenditures per student, eight in every nine has had litigation since 1973, and all nine of the Census Bureau’s defined Northeastern states are included in this grouping. Between the thirty-three states that maintain below average expenditures per student, eight in every nine has also had litigation filed since 1973, but more than one in every two come come from the American South and Southwest, each of which maintains the highest concentration of Black and Latino populations, respectively. These populations also come from houses with the lowest median household incomes, four times smaller than those of Whites, even when combining Black and Latino median households for a closer comparison. In other words, although litigation is associated with increased expenditures per student, more needs to be done in the way of evening out expenditures for students, especially in states where high minority populations attend the most underserved public schools in the nation.

In the past forty years, data from an abundance of sources (both federal and state) has indicated that progress is occurring in realms of student achievement, school attendance, demographics, and graduation rates. High school graduation rates have reached over 80 percent nationwide. Schools in 2012 spent $1,060 more per student than they did in 2001, a rate increase of over $88 per year. These numbers are laudable. But until the weighted public school funding system is balanced by more funding for low-income, majority-minority public schools and close off the pipeline between prisons and public schools, we shouldn’t expect any laurels.